Prince Maximilian of Baden

| Prince Maximilian of Baden | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Max von Baden in 1914 | |||||

| Head of the House of Baden | |||||

| Tenure | 9 August 1928 – 6 November 1929 | ||||

| Predecessor | Frederick II, Grand Duke of Baden | ||||

| Successor | Berthold, Margrave of Baden | ||||

| Born | 10 July 1867 Baden-Baden, Grand Duchy of Baden | ||||

| Died | 6 November 1929 (aged 62) Salem, Weimar Republic | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Princess Marie Alexandra of Baden Berthold, Margrave of Baden | ||||

| |||||

| House | Baden | ||||

| Father | Prince Wilhelm of Baden | ||||

| Mother | Princess Maria Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg | ||||

| Chancellor of Germany | |||||

| In office 3 October 1918 – 9 November 1918 | |||||

| Monarch | Wilhelm II | ||||

| Preceded by | Georg von Hertling | ||||

| Succeeded by | Friedrich Ebert | ||||

| Minister President of Prussia | |||||

| In office 3 October 1918 – 9 November 1918 | |||||

| Monarch | Wilhelm II | ||||

| Preceded by | Georg von Hertling | ||||

| Succeeded by | Friedrich Ebert | ||||

| Minister of Foreign Affairs of Prussia | |||||

| In office 3 October 1918 – 9 November 1918 | |||||

| Monarch | Wilhelm II | ||||

| Preceded by | Georg von Hertling | ||||

| Succeeded by | Office abolished | ||||

| Personal details | |||||

| Political party | Independent | ||||

Maximilian, Margrave of Baden (Maximilian Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm; 10 July 1867 – 6 November 1929),[1] also known as Max von Baden, was a German prince, general, and politician. He was heir presumptive to the throne of the Grand Duchy of Baden, and in October and November 1918 briefly served as the last chancellor of the German Empire and minister-president of Prussia. He sued for peace on Germany's behalf at the end of World War I based on U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points and took steps towards transforming the government into a parliamentary system. As the German Revolution of 1918–1919 spread, he handed over the office of chancellor to SPD Chairman Friedrich Ebert and unilaterally proclaimed the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II. Both events took place on 9 November 1918, marking the beginning of the Weimar Republic.

Early life

[edit]

Born in Baden-Baden on 10 July 1867, Maximilian was a member of the House of Baden, the son of Prince Wilhelm Max (1829–1897), third son of Grand Duke Leopold (1790–1852) and Princess Maria Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg (1841–1914), a granddaughter of Eugène de Beauharnais. He was named after his maternal grandfather, Maximilian de Beauharnais, and bore a resemblance to his cousin, Emperor Napoleon III.

Max received a humanistic education at a Gymnasium secondary school and studied law and cameralism at the Leipzig University. Upon the order of Queen Victoria, Prince Max was brought to Darmstadt in the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine as a suitor for Victoria's granddaughter, Alix of Hesse-Darmstadt. Alix was the daughter of Victoria's late daughter, Princess Alice, and Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse. Alix quickly rejected Prince Max, as she was in love with Nicholas II, the future Tsar of Russia.[2] Max von Baden was homosexual and even listed on an according list of the Berlin criminal police as a young officer, however in 1900 he decided for dynastic reasons to marry Princess Marie Louise of Hanover and Cumberland.[3] So did the future King Gustaf V of Sweden who married Max's cousin Victoria of Baden.

Early military and political career

[edit]After finishing his studies, he trained as an officer of the Prussian Army. Following the death of his uncle Grand Duke Frederick I of Baden in 1907, he became heir to the grand-ducal throne of his cousin Frederick II, whose marriage remained childless.[1] He also became president of the Erste Badische Kammer (the upper house of the parliament of Baden).[4] In 1911, Max applied for a military discharge with the rank of a Generalmajor (Major general).[4]

World War I

[edit]Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he served as a general staff officer at the XIV Corps of the German Army as the representative of the Grand Duke (XIV Corps included the troops from Baden).[4] Shortly afterwards, however, he retired from his position (General der Kavallerie à la suite) as he was dissatisfied with his role in the military and was suffering from ill health.[4][5]: 147

In October 1914, he became honorary president of the Baden section of the German Red Cross, thus beginning his work for prisoners-of-war inside and outside Germany in which he made use of his family connections to the Russian and Swedish courts as well as his connections to Switzerland.[4] In 1916, he became honorary president of the German-American support union for prisoners of war within the YMCA world alliance.[4]

Due to his liberal stance he came into conflict with the policies of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL – Supreme Army Command) supreme command under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. He openly spoke against the resumption of the unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, which provoked the declaration of war by the United States Congress on 6 April.

His activity in the interests of prisoners of war, as well as his tolerant, easy-going character gave him a reputation as an urbane personality who kept his distance from the extremes of nationalism and official war enthusiasm in evidence elsewhere at the time.[6] Since he was almost unknown to the public, it was mainly due to Kurt Hahn, who served from spring 1917 in the military office of the Foreign Ministry, that he was later considered for the position of chancellor. Hahn maintained close links with Secretary of State Wilhelm Solf and several Reichstag deputies like Eduard David (SPD) and Conrad Haußmann (FVP). David pushed for Max to be appointed Chancellor in July 1917, after the fall of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg. Max then put himself forward for the position in early September 1918, pointing out his links to the social democrats, but Emperor Wilhelm II turned him down.[6]

Chancellor

[edit]Appointment

[edit]After the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) told the government in late September 1918 that the German front was about to collapse and asked for immediate negotiation of an armistice, the cabinet of Chancellor Georg von Hertling resigned on 30 September 1918. Hertling, after consulting Vice-Chancellor Friedrich von Payer (FVP), suggested Prince Max of Baden as his successor to the emperor. However, it took the additional support of Haußmann, Oberst Johannes "Hans" von Haeften and Ludendorff himself to have Wilhelm II appoint Max as Chancellor of Germany and Minister President of Prussia.[6]

Max was to head a new government, based on the majority parties of the Reichstag (SPD, Centre Party and FVP). When Max arrived in Berlin on 1 October, he had no idea that he would be asked to approach the Allies about an armistice. Horrified, Max fought against the plan. Moreover, he also admitted openly that he was no politician, and that he did not think additional steps towards "parliamentarisation" and democratisation feasible, as long as the war continued. Consequently, he did not favour a liberal reform of the constitution.[6] However, Emperor Wilhelm II convinced him to take the post, and appointed him on 3 October 1918. The message asking for an armistice went out only on 4 October, not as originally planned on 1 October, hopefully to be accepted by US President Woodrow Wilson.[7]: 44

In office

[edit]Although Max had serious reservations about the conditions under which the OHL was willing to conduct negotiations and tried to interpret Wilson's Fourteen Points in a way most favourable to the German position,[6] he accepted the charge. He appointed a government that for the first time included representatives of the largest party in the Reichstag, the Social Democratic Party of Germany, as state secretaries (equivalent to ministers in other monarchies): Philipp Scheidemann and Gustav Bauer. This was following up on an idea of Ludendorff's and former Foreign Secretary Paul von Hintze's (as the representative of the Hertling cabinet) who had agreed on 29 September that the request for an armistice must not come from the old regime, but from one based on the majority parties.[7]: 36–37 The official reason for appointing a government based on a parliamentary majority was to make it harder for the American president to refuse a peace offer. The need to convince Wilson was also the driving factor behind the move towards "parliamentarisation" that was to make the Chancellor and his government answerable to the Reichstag, as they had not been under the Empire so far. Ludendorff, however, was more interested in shifting the blame for the lost war to the politicians and to the Reichstag parties.[7]: 33–34

The Allies were cautious, distrusting Max as a member of a ruling family of Germany. These doubts were intensified by the publication of a personal letter Max had written to Prince Alexander zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst in early 1918, in which he had expressed criticism of "parliamentarisation" and his opposition to the Friedensresolution of the Reichstag of July 1917, when a majority had demanded a negotiated peace rather than a peace by victory.[6] President Wilson reacted with reserve to the German initiative and took his time to agree to the request for an armistice, sending three diplomatic notes between 8 October and 23 October 1918. When Ludendorff changed his mind about the armistice and suddenly advocated continued fighting, Max opposed him in a cabinet meeting on 17 October 1918.[7]: 50 On 24 October, Ludendorff issued an army order that called Wilson's third note "unacceptable" and called on the troops to fight on. On 25 October, Hindenburg and Ludendorff then ignored explicit instructions by the Chancellor and travelled to Berlin. Max asked for Ludendorff to be dismissed; Wilhelm II agreed. On 26 October, the emperor told Ludendorff that he had lost his trust. Ludendorff offered his resignation and Wilhelm II accepted.[7]: 51

While trying to move towards an armistice, Max, advised closely by Hahn (who also wrote his speeches), Haußmann and Walter Simons, worked with the representatives of the majority parties in his cabinet (Scheidemann and Bauer for the SPD, Matthias Erzberger, Karl Trimborn and Adolf Gröber for the Centre Party, Payer and, after 14 October, Haußmann for the FVP). Although some of the initiatives were a result of the notes sent by Wilson, they were also in line with the parties' manifestos: making the Chancellor, his government and the Prussian Minister of War answerable to parliament (Reichstag and Preußischer Landtag), introducing a more democratic voting system in the place of the Dreiklassenwahlrecht (Three-class franchise) in Prussia, the replacement of the Governor of Alsace-Lorraine with the Mayor of Straßburg, appointing a local deputy from the Centre Party as Secretary of State for Alsace-Lorraine and some other adjustments in government personnel.[6]

Pushed by the social democrats, the government passed a widespread amnesty, under which political prisoners like Karl Liebknecht were released. Under Max von Baden, the bureaucracy, military and political leadership of the old Empire began a cooperation with the leaders of the majority parties and with the individual states of the empire. This cooperation was to have a significant impact on later events during the revolution.[6]

In late October, the Imperial constitution was amended to transform the empire into a parliamentary monarchy. The chancellor was now responsible to the Reichstag rather than the emperor. However, Wilson's third note seemed to imply that negotiations for an armistice would be dependent on the abdication of Wilhelm II. Max and his government now feared that a military collapse and a socialist revolution at home were becoming likelier with every day that went by. In fact, the government's efforts to secure an armistice were interrupted by the Kiel mutiny, which began with events at Wilhelmshaven on 30 October and the outbreak of revolution in Germany in early November. On 1 November, Max wrote to all the ruling Princes of Germany, asking them whether they would approve of an abdication by the Emperor.[6] On 6 November, the Chancellor sent Erzberger to conduct the negotiations with the Allies. Max, seriously ill with Spanish influenza, urged Wilhelm II to abdicate. The Emperor, who had fled from revolutionary Berlin to the Spa headquarters of the OHL in Belgium, despite similar advice by Hindenburg and Ludendorff's successor Wilhelm Groener of the OHL, was willing to consider abdication only as German Emperor, not as King of Prussia.[8] This was not possible under the imperial constitution as it stood. Article 11 defined the empire as a confederation of states under the permanent presidency of the king of Prussia. Thus, the imperial crown was tied to the Prussian crown, and Wilhelm could not renounce one crown without renouncing the other.[5]: 191

Revolution and resignation

[edit]On 7 November, Max met with Friedrich Ebert, leader of the SPD, and discussed his plan to go to Spa and convince Wilhelm II to abdicate. He considered installing Prince Eitel Friedrich, Wilhelm's second son, as regent;[7]: 76 however, the outbreak of the revolution in Berlin prevented Max from implementing his plan. Ebert decided that to keep control of the socialist uprising the Emperor must abdicate quickly and a new government was required.[7]: 77 As the masses gathered in Berlin, at noon on 9 November 1918, Maximilian went ahead and unilaterally announced Wilhelm's abdication of both the imperial and Prussian crowns, as well as the renunciation of Crown Prince Wilhelm.[7]: 86

Shortly thereafter, Ebert appeared in the Reichskanzlei and demanded that the government be handed over to him and the SPD, as that was the only way to keep up law and order. In an unconstitutional move, Max resigned and appointed Ebert as his successor.[7]: 87 On the same day, Philipp Scheidemann spontaneously proclaimed Germany a republic in order to placate the masses and prevent a socialist revolution. When Maximilian later visited Ebert to say goodbye before leaving Berlin, Ebert – who urgently wanted to keep up the old order, improving it through parliamentary rule, and head a legitimate, not a revolutionary government – asked him to stay on as regent (Reichsverweser). Maximilian refused and, turning his back on politics for good, departed for Baden.[7]: 90

Although events had overtaken him during his tenure at the Reichskanzlei and he was not considered a strong Chancellor, Max is seen today as having played a vital role in enabling the transition from the old regime to a democratic government based on the majority parties and the Reichstag. This made the government of Ebert that emerged from the November revolution acceptable to some conservative forces in the bureaucracy and military, which was one of Ebert's strongest aims. They were thus willing to ally themselves with him against the more radical demands by the revolutionaries on the far-left.[6]

Later life and death

[edit]Maximilian spent the rest of his life in retirement. He rejected a mandate to the 1919 Weimar National Assembly, offered to him by the German Democratic politician Max Weber. In 1920, together with Kurt Hahn, he established the Schule Schloss Salem boarding school, which was intended to help educate a new German intellectual elite.[4]

Max also published a number of books, assisted by Hahn: Völkerbund und Rechtsfriede (1919), Die moralische Offensive (1921) and Erinnerungen und Dokumente (1927).[6]

In 1928, following the death of Grand Duke Frederick II, who had been deposed in November 1918 when the German monarchies were abolished, Maximilian became head of the House of Zähringen, assuming the dynasty's historical title of Margrave of Baden. He died at Salem on 6 November the following year.[4]

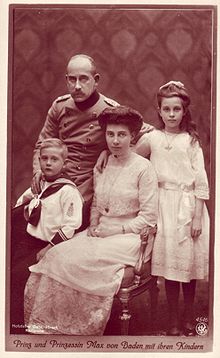

Children

[edit]Maximilian was married to Princess Marie Louise of Hanover and Cumberland, eldest daughter of Ernest Augustus, Crown Prince of Hanover, and Thyra of Denmark, on 10 July 1900 in Gmunden, Austria-Hungary. The couple had two children:[1]

- Princess Marie Alexandra of Baden (1 August 1902 – 29 January 1944); married Prince Wolfgang of Hesse, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, son of Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse-Kassel, designated King of Finland, and Princess Margaret of Prussia; no issue. Marie Alexandra was killed in a bombing of Frankfurt by the Allies of World War II.

- Prince Berthold of Baden (24 February 1906 – 27 October 1963); later Margrave of Baden; married Princess Theodora, daughter of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg. Theodora was the sister of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

Titles, styles and honours

[edit]Titles and styles

[edit]- 10 July 1867 – 8 August 1928: His Grand Ducal Highness Prince Maximilian of Baden[1]

- 9 August 1928 – 6 November 1929: His Royal Highness The Margrave of Baden[1]

Honours

[edit] Baden:

Baden:

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity[11]

- Knight of the Order of Berthold the First[12]

- Knight of the Zähringer Lion, 1st Class

- Commander of the Military Karl-Friedrich Merit Order, 1st Class, 30 August 1914

- Friedrich-Luise Medal

- Commemorative Medal for the Golden Jubilee of Grand Duke Friedrich I and Grand Duchess Luise

Anhalt: Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 1889[13]

Anhalt: Grand Cross of Albert the Bear, 1889[13] Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1899[14]

Bavaria: Knight of St. Hubert, 1899[14] Hanoverian Royal Family: Knight of St. George

Hanoverian Royal Family: Knight of St. George

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order Hesse and by Rhine: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 6 May 1892[15]

Hesse and by Rhine: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 6 May 1892[15] Mecklenburg: Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore

Mecklenburg: Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown

Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1885[16]

Württemberg: Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1885[16] Prussia:

Prussia:

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle, 27 September 1898[17]

- Knight of the Black Eagle, with Collar, invested 18 January 1903[18]

- Grand Commander's Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern

- Iron Cross (1914), 2nd Class

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class

Hohenzollern: Cross of Honour of the Princely House Order of Hohenzollern, 1st Class

Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1900[19]

Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1900[19] Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (military), 2 October 1906[20]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (military), 2 October 1906[20] Bulgaria: Grand Cross of St. Alexander

Bulgaria: Grand Cross of St. Alexander Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 10 July 1900[21]

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant, 10 July 1900[21] Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I

Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I Russia: Knight of St. Andrew

Russia: Knight of St. Andrew

Sweden-Norway:

Sweden-Norway:

- Grand Cross of St. Olav, 30 August 1887[22]

- Knight of the Seraphim, 24 April 1902[23]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Prince Maximilian of Baden |

|---|

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Almanach de Gotha. Haus Baden (Maison de Bade). Justus Perthes, Gotha, 1944, p. 18, (French).

- ^ Massie, R, Nicholas and Alexandra, p.49

- ^ Lothar Machtan: Prinz Max von Baden. Der letzte Kanzler des Kaisers. Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-518-42407-0, p. 243f and 253f.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Biografie Prinz Max von Baden (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b Watt, Richard M. (2003). The kings depart : the tragedy of Germany : Versailles and the German revolution. London: Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-658-X. OCLC 59368284.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Biografie Prinz Max von Baden (German)". Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Haffner, Sebastian (2002). Die deutsche Revolution 1918/19 (German). Kindler. ISBN 3-463-40423-0.

- ^ Wilhelm II (1922). The Kaiser's Memoirs. Translated by Thomas R. Ybarra. Harper & Brothers Publishers. pp. 285-91.

- ^ a b Rangliste der Königlich Preußischen Armee und des XIII. (Königlich Württembergischen) Armeekorps für 1914. Hrsg.: Kriegsministerium. Ernst Siegfried Mittler & Sohn. Berlin 1914. S. 355.

- ^ a b Lothar Machtan: Prinz Max von Baden: Der letzte Kanzler des Kaisers. Suhrkamp Verlag. Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3-518-42407-0. p. 246.

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1896), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 61

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch ... (1896), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 76

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch für des Herzogtum Anhalt (1894), "Herzoglicher Haus-Orden Albrecht des Bären" p. 17

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Bayern (1906), "Königliche Orden" p. 9

- ^ "Ludewigs-orden", Großherzoglich Hessische Ordensliste (in German), Darmstadt: Staatsverlag, 1914, p. 5 – via hathitrust.org

- ^ Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Königreichs Württemberg 1907. p. 30.

- ^ "Rother Adler-orden", Königlich Preussische Ordensliste (in German), Berlin, 1895, p. 8 – via hathitrust.org

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Germany". The Times. No. 36981. London. 19 January 1903. p. 5.

- ^ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Liste des Membres de l'Ordre de Léopold", Almanach Royale Belgique (in French), Bruxelles, 1907, p. 86 – via hathitrust.org

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 463. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- ^ Norges Statskalender (in Norwegian). 1890. pp. 595–596. Retrieved 2018-01-06 – via runeberg.org.

- ^ Sveriges Statskalender (in Swedish). 1925. p. 813. Retrieved 2018-01-06 – via runeberg.org.

External links

[edit]- CS1: unfit URL

- 1867 births

- 1929 deaths

- 19th-century German LGBTQ people

- 20th-century chancellors of Germany

- Foreign ministers of Prussia

- Generals of Cavalry (Prussia)

- German Empire politicians

- German monarchists

- German people of World War I

- Heidelberg University alumni

- House of Zähringen

- People from Baden-Baden

- People from the Grand Duchy of Baden

- Princes of Baden

- Prussian politicians

- Pretenders

- LGBTQ royalty

- German LGBTQ politicians

- 20th-century German LGBTQ people

- LGBTQ military personnel

- LGBTQ Protestants

- Heirs presumptive

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary

- Recipients of the Iron Cross, 2nd class

- Leipzig University alumni